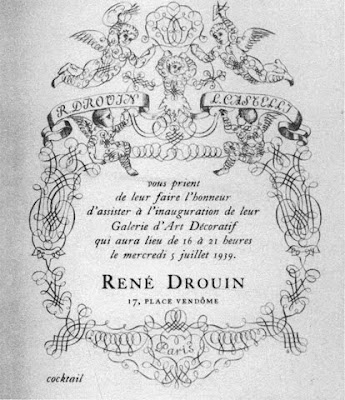

On July 5, 1939, an imposing new art gallery opened in Paris next to the Schiaparelli fashion house, at 17 Place Vendome, with a fare of strangely shaped armoires and chairs with trompe l’oeil decorations, sleek-looking modern pieces and old ones made-to-look-like-new, plus at least one famous painting by Max Ernst. The invitation to the inauguration came from R. Drouin and L. Castelli, two men in their late 30s who had become friends through their respective wives, Ileana and Olga, who were both natives of Romania. René Drouin was a French interior designer, while Leo Castelli, who would of course become a famous art dealer in New York more than two decades later, was then a man-about-town married to a wealthy young heiress from Bucharest, living a carefree life in Paris. He was financing the new gallery. Neither Drouin nor Castelli knew much about modern art, and their tastes were quite opposite.

~Invitation to the opening exhibition at the Rene Drouin Gallery |

How did this inexperienced team pull off a show that has recently been hailed by Ghislaine Wood, an expert in Surrealist applied arts, as "the height of Surrealism in design"? How did Castelli, a Paris newcomer, attract the best known figures of the decadent Parisian upper crust of the ‘30s to a show about Surrealist interiors? Why is it that this pioneering exhibition has remained under the radar, at least until an exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum in 2007 entitled "Surreal Things, Surrealism and Design?"

My interest in the Drouin Gallery began as I worked on my book Artists under Vichy(Princeton, 1992), and led me to interview Leo in June 1986 on his gallery’s prewar activities in Paris. That conversation provides some details and leads that I followed up in search of answers to these tantalizing questions.

While living in Bucharest, Leo Castelli and Ileana attended a reception at the French embassy. There the couple met Drouin, who had worked on the redecoration of that embassy. When the Castellis moved to Paris, they reconnected with Drouin and his wife Olga. With money to burn, they first asked Drouin to decorate their posh new apartment in Neuilly.

~Eugene Berman Wardrobe 1939 Virginia & Albert Museum

As there are no photographic traces of the Castellis’ Neuilly home designed by Drouin, I asked Leo what he remembered so I could better understand Drouin’s esthetic sensibility. The Castelli apartment was on the rue St. James, a secluded corner of Neuilly with lots of private gardens. The décor was "very spare, full of light, with beautiful antique sconces, light color, with nothing on the walls." Were it not for the antique sconces, the interior could have been signed Le Corbusier. Drouin had indeed studied with Corbu, and moved among architects, designing metal furniture for them. He was also a contributor toL’Architecture d’aujourd’hui, a well-regarded and progressive publication whose editor was André Bloc.

After a while, the friendship of the two men apparently took a more professional turn, and the idea of opening a new kind of gallery germinated. On how Castelli and Drouin came to lease the space on Place Vendome, my interview with him also offers fresh details. Apparently the two of them were walking around the Place Vendome, perhaps to meet their wives at the Schiaparelli fashion house, when they noticed a "for rent sign," at no.17. "On that fatal day," Castelli remembers, "we went in to see, spoke to a Ritz employee because the gallery belonged to the hotel; Knoedler had been there but the gallery had left to concentrate on England." Earlier in the century, the art dealer Jacques Seligmann had been the tenant of that space.

~Salon of Carlos de Beistegui’s apartment, Paris, 1930. Illustrated in Architectural Review, April 1930

"The space," he volunteered "was very beautiful, it had marble floors, large columns, five rooms en enfilade, high ceilings , and windows that overlooked the garden of the Ritz. It also had a basement and a sub-basement. And the rent was very inexpensive." "We were young and light-hearted, kids pursuing our dreams. . .Inconscience juvénile," Leo added in French. They consulted with Leo’s father-in- law who said "yes, how much?" They asked for 500,000 francs. In 1938, this amounted to 15,000 dollars, according to Leo, who told me that every franc had been spent by the time the show closed.

And now came the question of what to show in this elegant space. The idea of showing modern furniture, as well as antiques -- more Leo’s and Ileana’s domain, was their starting point. Drouin would provide the modern furniture, and Leo and Ileana, who loved antiquing on the rue Jacob, would contribute the unusual objects. "A Victorian settee, Louis XVI chairs, odd tables, silver pieces, whatever serendipidy placed in front of us," he told me. That was the plan until they met Leonor Fini, born like Leo in Trieste. Beautiful, talented and rich, Fini, had made her way into the Surrealist milieu, and was showing her paintings with theirs.

Although Fini had been briefly a girlfriend of Max Ernst, a Surrealist of the first hour, she did not share the Surrealists’ enmity to bourgeois values, letting neo-romantics like Eugene Berman into her Surrealist camp, and she happily joined the world of fashion, drawing designs for Schiaparelli and Balenciaga, wearing their clothes and comingling with Parisian high society. Leo says that she helped him understand Surrealism. She no doubt steered him away from the art deco style of interior decor, and enticed the Surrealists to approach him with fantasy designs like Dali’s inflatable chair, and quantities of amusing though impractical functional objects. She was also a useful go-between with the Parisian upper crust.

~Le Corbusier, apartment of Carlos de Beistegui, 7th-9th floors of 136 Champs-Elysees, Paris, 1930. Fondation Le Corbusier, Paris

Drouin was hardly enthusiastic about the invasion of Surrealism. "He was too much of a purist," says Leo. It is also the case that in the late 1930s, the fashionable set was tired of the techno/modernity of art deco. With Castelli sensing that the wind was shifting, Fini won out, and the show that she helped to orchestrate opened on July 5, 1939. As recounted by Castelli’s biographer, Annie Cohen-Solal, "the exhibition had an undisputable success in the foreign press." (p. 135) To Paul Cummings, Castelli offered the following memories of the show: "Leonor Fini and Berman did two special painted cupboards. . . . Berman’s was a rather sinister setting that looked like a wild landscape, like something out of Canaletto, or rather Gaudi. . . . Then Meret Oppenheim designed a table with legs that were the legs of some animal or bird -- and a hand mirror that was all like hair, like locks. Leonor Fini designed tall panels with all kinds of heraldic figures. There was all that antique furniture and then the modern furniture of Drouin’s."

Among the 2007 Victoria & Albert Museum offerings were the pieces that Leo calls "cupboards," in fact bizarrely-shaped and decorated armoires by Fini and Berman, Meret Oppenheim’s oval tabletop supported by long gilded birds’ legs (though not the hand-mirror in hair mentioned by Leo). It had Fini’s panels with heraldic figures (self portraits), and it had pieces that Leo did not mention, such as Fini’s wrought iron Corset Chair.

~Leonor Fini Le Peinture (Painting) / L’Architecture (Architecture) 1939 Collection of Rowland Weinstein

Opening night according to Castelli was "brilliant and decadent." The Noailles, the de Beaumonts, and Carlos de Beistegui were among the high society attendees. Charles de Noailles, though gay, was married to a wealthy hostess and patron of the Surrealists. Etienne de Beaumont also led a double life, and was the organizer of extravagant costumed balls. As for Carlos de Beistegui, who had money to burn, he collected boyfriends and homes.

In 1930, Corbusier had designed for this wealthy Mexican heir an apartment on Avenue des Champs Elysées that signaled a new sensibility. Though the architect had placed one of his archetypal white cubes on top of an existing older building, the spaces he had created exuded the eerie emptiness of a painting by Magritte, and the terraces intentionally stirred confusion between outdoor and indoors, between upstairs and downstairs, between the present and the past -- this last feature provided by the neo-rococo sofas and chests by Emilio Terry. It was recently rediscovered, and exemplifies the Surreal interior.

~Leonor Fini Armoire anthropomorphe 1939 Collection of Roland Weinstein

If the natural affinity of the Surrealists for interiors in their paintings has, thanks to Ghislaine Wood, been fully and brilliantly examined in her catalogue essay for the "Surreal Objects" exhibition,* the fascination of a certain set of Parisian aristocracy for Surrealist interiors is still something of a mystery. For Wood, the Surrealist interior interpreted through a Freudian lens "no longer signified domesticity and security, but carried an image of more disturbing and sexualized meanings. . . " (p.40). She suggests that the Surrealist depictions of the home, offering neither domesticity nor security, reflected a feminist rebellion, and she gives as examples paintings of surrealist interiors by Carrington,Toyen, Dorothea Tanning.

But what about the patrons of Surrealist interiors? While the Surrealist concept of a livable interior which "provides neither domesticity nor security" might appeal to liberated young women, the Freudian view of home as an unheimlich place, a refuge from conventional home life, and a mysterious dangerous place for secret rendez vouswhere anything can happen, suggests another type of afficionado: The very individuals that Castelli names among the guests at the opening, a group of men who led double lives and whosemores were anything but wholesome.

~Leonor Fini Corset Chair 1939 Private Collection

By today’s standards, the Castelli/Drouin show blurring the boundary between the old and the new, the functional and the quirky has prophetic resonances -- yet in the Surrealist literature, the show was long overshadowed by other Surrealist events in Paris earlier in the 1930s. Was it Castelli himself who belittled it as an amateurish endeavor of his youth? Or were there other reasons why this event long remained under the radar. Its timing for one, so close to the declaration of war between France and Germany, sends negative vibes. Was it not insensitive and irresponsible for anyone, particularly a rich foreigner, to start a frivolous enterprise at a time of grave uncertainty, when other art galleries were closing shop? Also, was the snob address of the gallery and the leftist politics of the original Surrealist movement a contradiction? If anything, a show of interiors dominated by Surrealist creations suggested a betrayal of the Surrealist ideal as a way of conducting oneself in the world.

~Meret Oppenheim Table with Bird’s Legs 1939 Private Collection

The disappearance of the show from art history may have a simple explanation. World War II and the debacle disrupted everything. Drouin was drafted into the army. Max Ernst was interned as an enemy alien at the Camp des Milles, and eventually managed to leave France. Leonor Fini left for Monte Carlo. Castelli followed his in-laws to the south of France and to New York. Then, after the Armistice was signed, and Paris was occupied by the Nazis, cultural activities resumed, but with new creators and new patrons. The Drouin gallery was reborn, as an art gallery with a director named Georges Maratier. In interior design, the 40s heralded a new style, opulent-looking furniture coded "nouveau retro" (some called it Louis XVII for a French monarch that never reigned) by Serge Roche, Gilbert Poillerat, Andre Arbus, Emilio Terry (See Cone, "Wartime Gilt, French Furniture of the ‘40s," Art in America, September 1999.)

In the end, the story of the July 1939 show of decorative arts at Drouin on Place Vendome reveals personality traits that Castelli was later to use even more successfully in New York: A nose for talent, an ability to choose his advisers well, a flexibility that allowed him to see the winds of art shifting direction, and a way to ingratiate himself to the right people. One mystery remains: Why did it take Leo so long to reassert these talents in New York? Was New York a tougher nut to crack in the ‘50s than Paris was in the late ‘30s?

~Salvador Dalí Mae West's Lips Sofa 1936-7 Private collection

*See the chapter The Illusory Interior in Surreal things, Surrealism and Design (V&A Publications, 2007).

MICHÈLE C. CONE is a New York-based critic and historian. Her latest book is French Modernisms: Perspectives on Art before, during and after Vichy(Cambridge 2001).

No comments:

Post a Comment